Section 1.1.

Early Marketing of “The Country Club District”

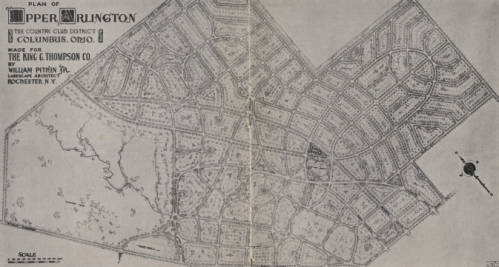

In 1914 King Thompson promoted the fledgling Upper Arlington community as “The Country Club District” which offered “a thousand acres of restricted land.”(1) In the modern era, this suggests an uncomfortable degree of exclusivity. What were Thompson’s plans as he took on the largest real estate development project of his career?

The 36-page marketing brochure published in 1914 by The King Thompson Company offers unparalleled insight into his endeavors.

From his previous experience developing land north of Columbus, Thompson acknowledged “the futility of trying to create an ideal neighborhood by the development of a forty, fifty or even a hundred-acre tract when they had no control over the surrounding land.”(2) His lack of control resulted in seeing nearby store buildings which would “project beyond the building lines of fine houses, ruining the vistas down beautiful avenues.”(3) In fact, Thompson promised early on in the 1914 brochure that for this project “the entire area will be laid out in plan first, each section being designed in relation to the whole” to “avoid haphazard growth.”(4) In other words, he wanted full control in designing a community according to his vision.

The restrictions for the young community (today roughly bounded by W. Lane Avenue, Andover Road, Fifth Avenue and Riverside Drive) were explained on pages 24-26 as follows:

Areas for parks (hence the “pocket parks” that are found south of Lane Avenue today)

Large lots with spacious grounds for homeowners

Specified setbacks from the street for homes

No apartments or double houses allowed

Limited commercial properties

Notably absent from his definition of “restricted” is racial exclusions. In fact, research from the Upper Arlington Historical Society has revealed that property deeds issued in the Historic District through August of 1926 did not contain racial covenants.

Racial restrictions were added to deeds starting in September 1926, and the reason is unknown to date. Were restrictions assumed but not documented prior to that point? Were there financial or other institutional incentives for doing so? These answers remain to be discovered.

Also noteworthy in this brochure was Thompson’s expressed desire for a “better class of homes” to be within the reach of those “compelled to buy on smaller payments” and allow for a wide range of price points, implying a more economically-diverse customer base than typically regarded.(5)

References:

(1) “The Country Club District,” The King Thompson Company: Columbus (OH) 1914.

https://www.uaarchives.org/digital/collection/p15062coll1/id/5687/rec/8, p. 3

(2) Ibid, p. 10-11

(3) Ibid, p. 7

(4) Ibid, p. 3, 5

(5) Ibid, p. 4